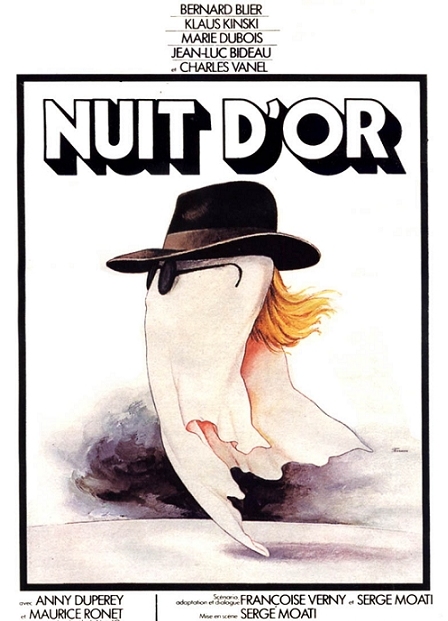

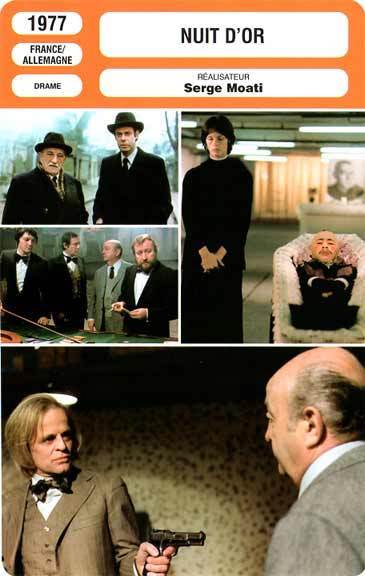

A fitfully inspired but ultimately pointless work from French filmmaker Serge Moati, Nuit d’or (1977) is an extremely odd little duck. Taking inspiration from works as random as John Boorman’s neo-noir classic Point Blank (1967) and Joe D’Amato’s mesmerizing Death Smiles on a Murderer (1973), while failing to match the brilliance of either of those films, Nuit d’or is a sort of revenge thriller strangely light on thrills and vengeance.

Countless films, books, and plays have told stories focused on characters back from a supposed death bent on revenge. An ideal trope for both crime and supernatural-based works, this vengeful genre has produced truly great works across a variety of artistic fields, but it is also amongst the most overused. Nuit d’or (Golden Night) is an interesting addition, but ultimately it fails to distinguish itself from the many better films it owes so much to.

Born just after World War 2 in Tunis, France, Serge Moati has had a hell of a strange career that’s found him working in a variety of capacities in the French film industry. His first credit was on screen via his appearance as one of Antoine Doinel’s schoolmates in Francois Truffaut’s monumental The 400 Blows (1959). He’s racked up a couple of dozen performances in his career and that helped him land some television presenter gigs later, but most of his work has been behind the camera, including as a credited screenwriter on Jean Rollin’s The Nude Vampire (1970).

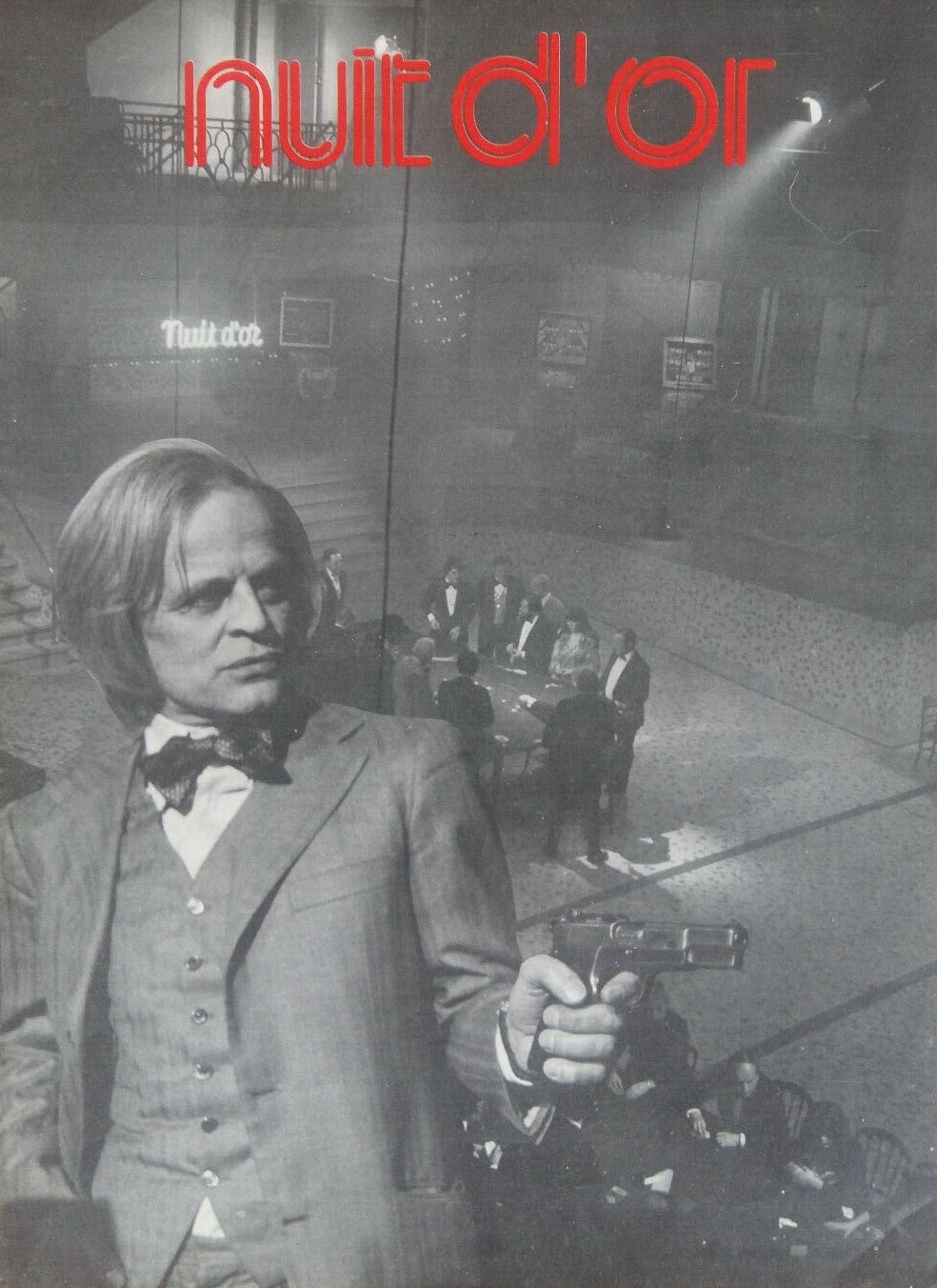

Moati’s work leading up to and directly after Golden Night was in French television with his 1976 feature appearing out of nowhere. With that in mind, Golden Night is stylistically at least pretty impressive. Moati’s restless and roaming camerawork gives Golden Night a fluid feel and at less than 90 minutes, it breezes by, never feeling at all lethargic. Sadly, the script credited to Moati and Francoise Verny is beyond aimless. The whole film feels like an introduction, a prelude that fails to fulfill a promise.

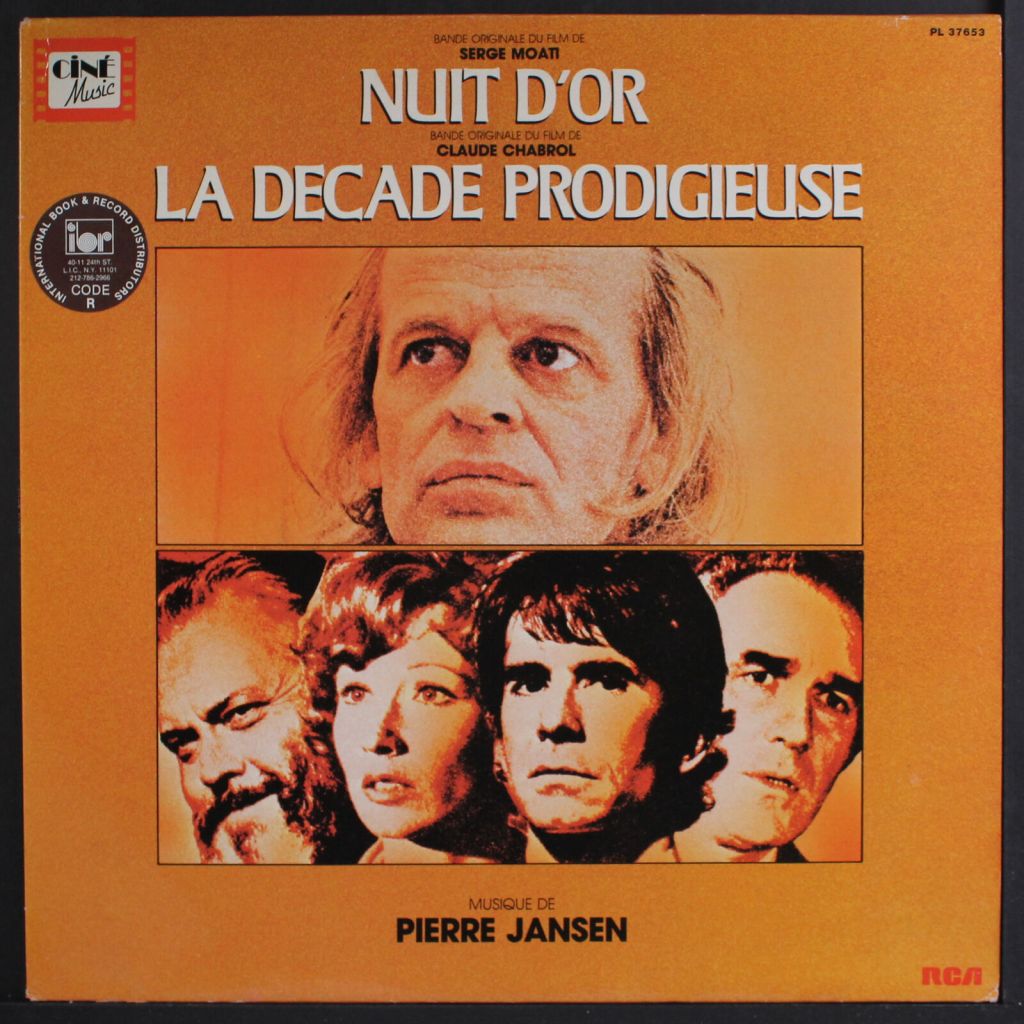

Golden Night has as many pleasures as it does faults. Packed with some wonderfully memorable actors like Klaus Kinski, Maurice Ronet, Marie Dubois, and scene-stealing Anne Duperey, Golden Night is not lacking on-screen talent. Nor is it lacking visually, as Moati’s film is an incredibly handsome production photographed remarkably well by André Neau. Nicely scored by frequent Claude Chabrol composer Pierre Jansen assisted by Jean Schwarz, Golden Night stylistically fits in well with the other many European art house films of the period but ultimately it is just an odd cinematic head-scratcher.

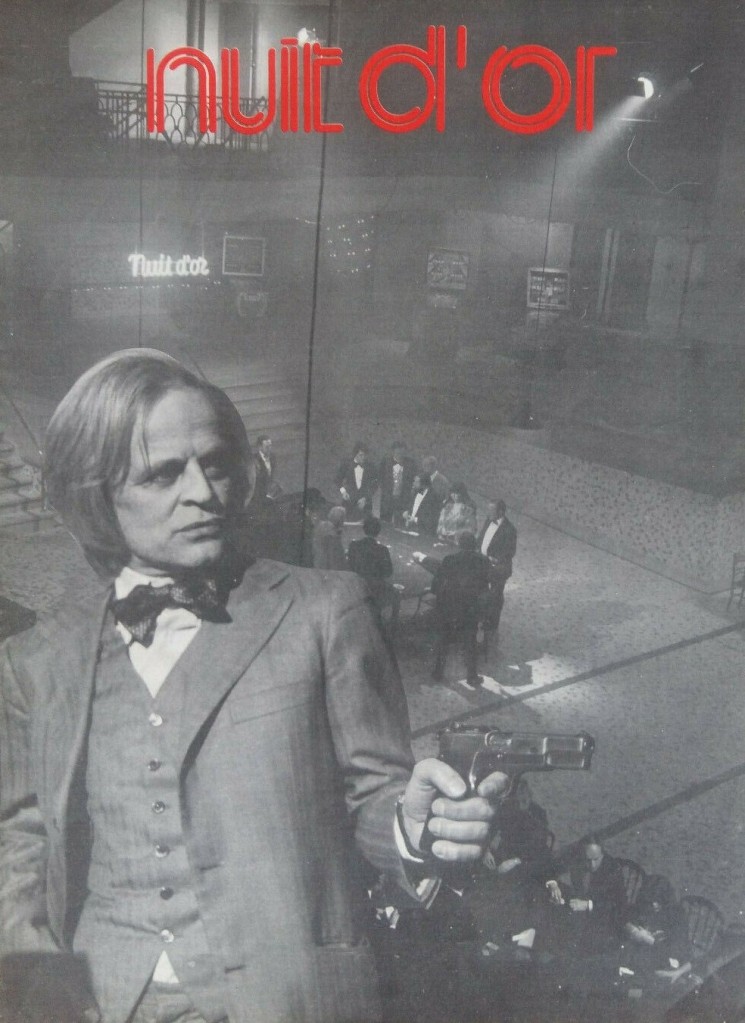

Klaus Kinski had appeared in works centered on the idea of a vengeful spirit via his appearances in the aforementioned D’Amato film along with Jess Franco’s earlier Venus in Furs (1967) but unlike those films where he played an object of vengeance here, Kinski plays the specter himself. Thing is, though, Golden Night never works as a revenge thriller, nor does it work as a supernatural vehicle as Moati can never seem to fully commit to either genre. Golden Night is a confusing and muddled work whose stylistic appeal can’t hide its basic structural and plot problems.

Klaus Kinski, by the mid-seventies, was both one of the world’s best actors along with its laziest. Treating most of the films he appeared in with overt disdain, Kinski simply made a habit of sleepwalking through roles he just took for the money. Kinski is in listless mode throughout Golden Night, but to his credit, Moati makes it work for the film. Even an uninterested Kinski is an interesting screen presence and his natural terrifying charisma comes through in Golden Night despite the script giving him next to nothing to work with.

The fine supporting cast found in Golden Night has very little to do. I’m a big fan of deliberately ambiguous films where not much happens in this period, but Golden Night’s problems don’t feel deliberate. They just feel baffling. The whole film feels confused and by the time the final predictable scene comes, it is hard not to shake the feeling of being cheated.

Golden Night briefly comes alive during a bizarre third-act turn involving a religious cult, but Moati fails to connect it successfully with the rest of his muddled narrative. Regardless, this subplot gives the film its most intriguing moments and its most interesting character, played wonderfully well by Anne Duperey. 1977 was a big year for the incredibly talented Duperey as she would land a Cesar nomination for her work in Pardon Mon Affaire as well her English language breakthrough in Bobby Deerfield. Duperey’s performance is easily the best thing about Golden Night and she is a much more commanding presence than Kinski. In fact, I would venture to say that Golden Night could have been a much better film had Moati switched their roles.

A French/German coproduction, Golden Night didn’t make an impact critically or financially upon its release and Moati mostly retreated to the world of television. Golden Night managed some festival appearances, including a slot at the Festival Internation du Film where The Montreal Star critic Martin Malena called its plot ‘flimsy’ but praised its ‘expressionistic style’ as ‘exhilarating’. Featured at a few more festivals up through 1978, Golden Night played at a handful of theaters in New York, California, Canada and Britain, but I’ve not seen any evidence of a wide release outside of France.

As it stands, Golden Night is an interesting failure although I’d give it a very light recommendation to anyone interested in European Art House films from this period. Considering how much love I have for this era and type of esoteric filmmaking, I found Golden Night particularly frustrating as all the ingredients were there for something utterly unique and special. Oh, well…

Jeremy Richey, January, 2024-

Leave a comment