Few filmmakers have ever fallen from critical and popular grace as far and fast as British-born director Hugh Hudson. Born of a prosperous London family in 1936, Hudson’s early career was especially promising initially as a documentarian and advertiser. Hudson received his first break in feature-length filmmaking when he acted as the Second-Unit Director on Alan Parker’s chilling Midnight Express (1978). Within a year of working with Parker, Hudson got his chance to sit in the lead director’s chair for a period-piece focusing on two runners training for spots in the 1924 Olympic Games. That film was Chariots of Fire, and it immediately became one of the most acclaimed films of its time. Still in his early forties, Hudson seemed geared to become one of the eighties most acclaimed filmmakers but then everything fell apart.

After losing the Best Director Oscar for Chariots of Fire in 1982 Hudson immersed himself in his next project, Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan (1984). The shoot was grueling and was strife with problems and the behind-the-scenes issues stretched to the screen, as Hudson’s follow-up to Chariots of Fire proved to be a major critical and financial letdown, despite its own unique powers. The lukewarm reception granted to Greystoke was nothing compared to the crucifying Hudson took for his third film, Revolution (1985), a brilliantly bold but flawed work that all but ended Hudson’s time as filmmaker any studio would bank on, even though he had helmed a best-picture winner less than five years before. Hudson and Revolution eventually had their revenge decades later via an acclaimed director’s cut but in 1985 they were toxic.

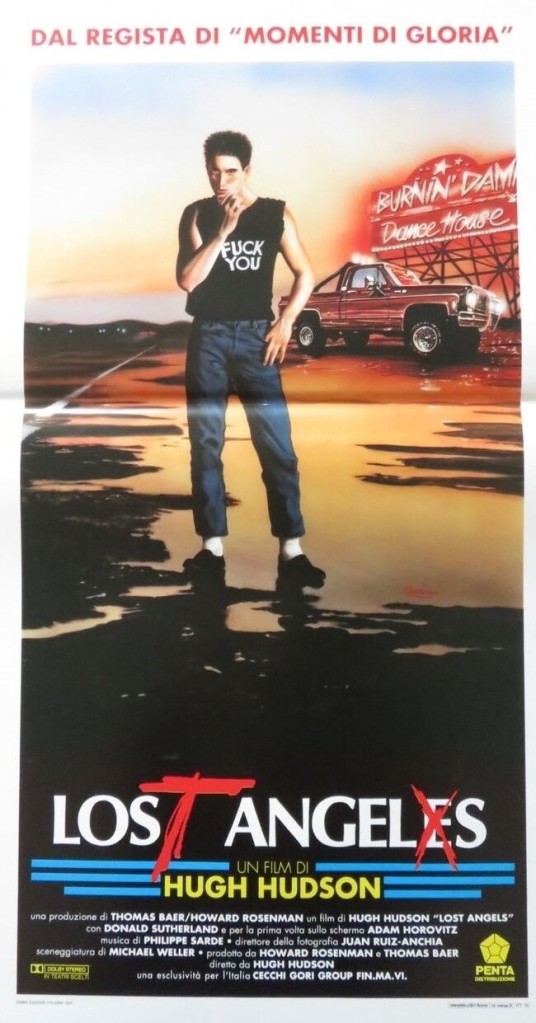

Disillusioned and embittered after the troubles he had with the studios on both Greystoke and Revolution, Hugh Hudson stepped away from the world of film for several years to regroup artistically and spiritually. He re-emerged in 1989 with a moving independent low-budget drama centering on a troubled young teen named Tim, but few took notice, and the still-stirring Lost Angels has all but slipped into obscurity.

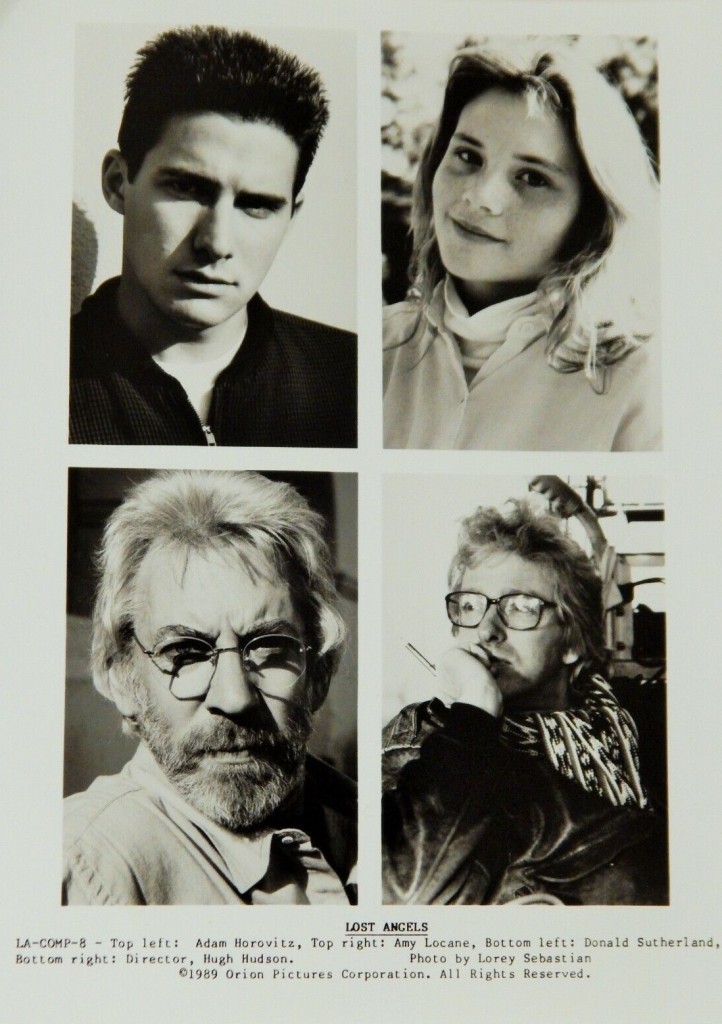

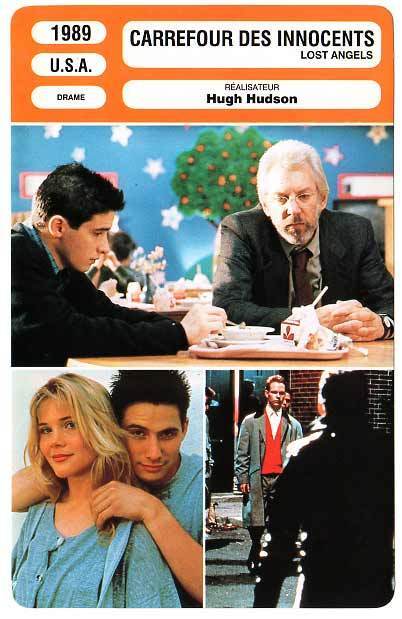

In Lost Angels Adam Horovitz plays Tim Doolan, an angry and frustrated teen who is committed to a psych hospital after continually getting in trouble at home and at school. While inpatient, Tim meets an understanding psychiatrist named Charles Loftis (played wonderfully by the great Donald Sutherland) and the two form a strong, if unexpected, mutually healing bond.

Shot around San Antonio, Texas, the gritty and small-scale Lost Angels was a real left-turn from the bold big-budget period-pieces Hudson was known for in 1989. Despite this, he guides the film with assured confidence and fluid style. Most surprising is the fact that Hudson showed his real gift as a director could be found in the way he handled his actors in intimate and sometimes uncomfortable-to-watch situations. Lost Angels has all the heart found in Chariots of Fire without the bombast and it stands as a sharp reminder that the late Hugh Hudson was a talent to be reckoned with.

The final script produced for the big screen penned by Oscar nominated writer Michael Weller, a man who won much acclaim for his work on Ragtime (1981), Lost Angels could have been just another Rebel Without a Cause clone but Weller’s script is really fine and especially in the moments between Tim and Loftis is really quite great. Weller’s dialogue is finely-tuned and really taps into what it was like to be an angry and disillusioned Reagan-era youth. Lost Angels stands out among the many angsty troubled-youth films of the late eighties and it’s a shame that it isn’t more well-known.

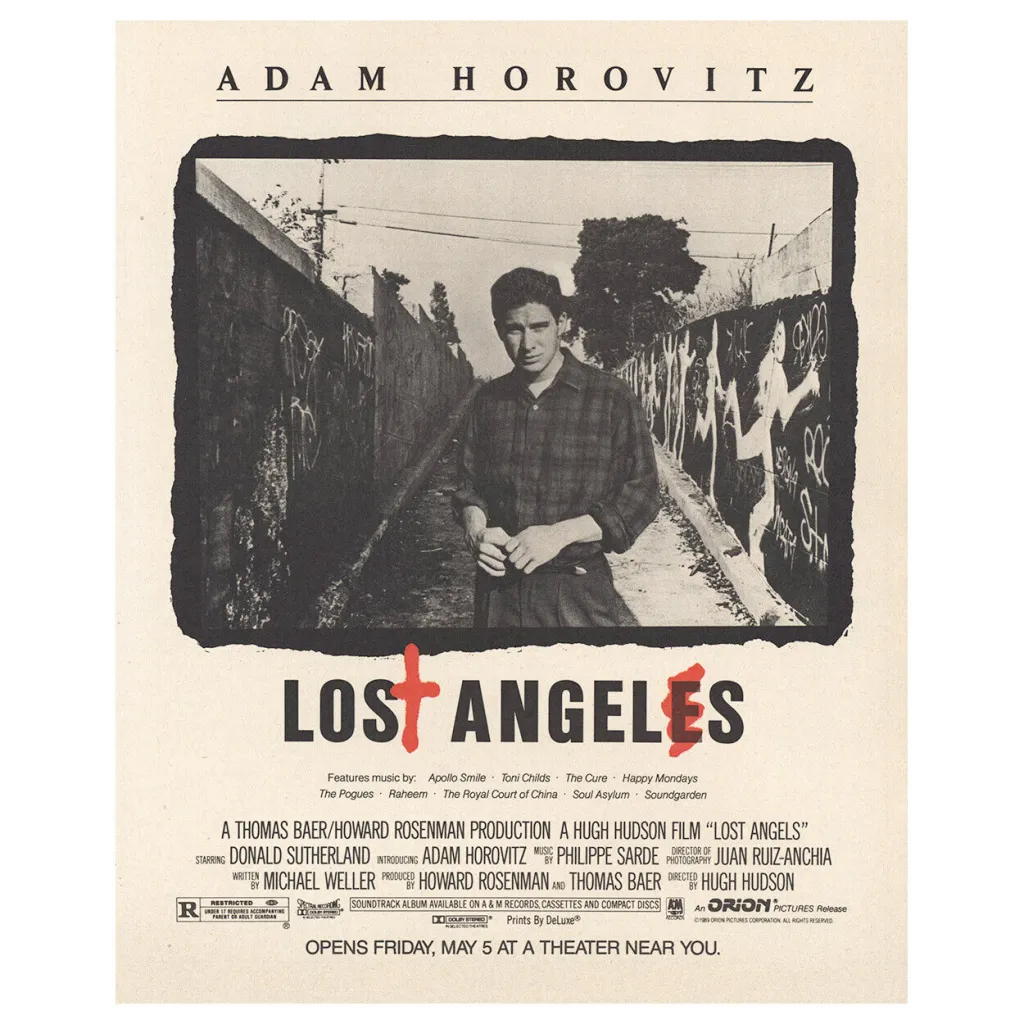

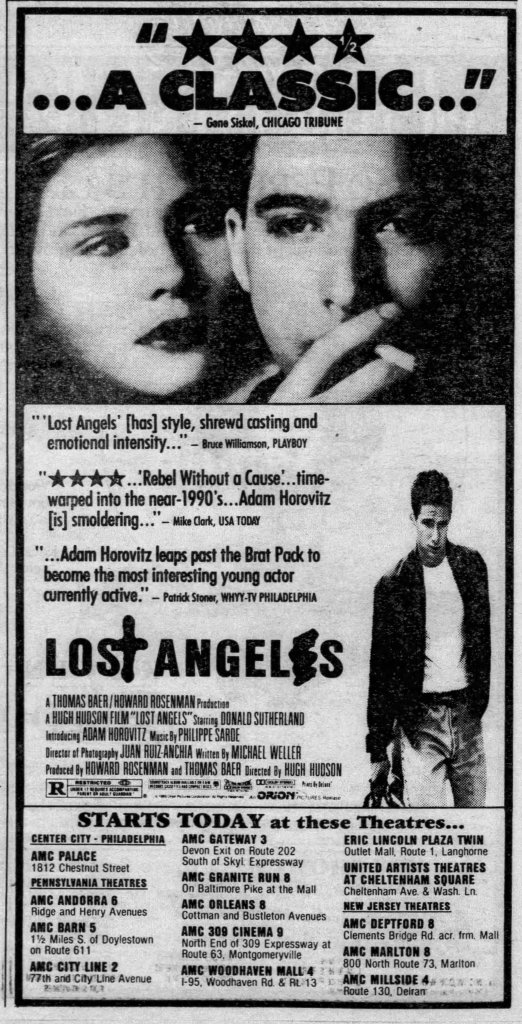

Shot by the wonderful Spanish cinematographer Juan Ruiz Ancjia, scored by none other than Philippe Sarde and featuring startling art-direction from legendary Alex Tavoularis, Lost Angels feels like a work of love from all involved, especially considering its low-budget and quick-shooting schedule. It’s moving, beautifully acted and directed and was all but ignored despite a theatrical push by Orion in May of 1989. Despite the fact that it had been nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes, Lost Angels failed to find much critical or popular support upon its release and Hugh Hudson’s valiant attempt at resurrecting his film career sadly did not pay-off.

Hudson personally chose the young actor for lead role Tim in Lost Angels after a fairly lengthy search and it turned out an inspired pick. Had he not been a member of one of the most consistently brilliant groups of the last four decades, Beastie Boy Adam Horovitz (Ad-Rock) could have had quite a film career, as he has both the looks and talent of a great star. Horowitz has appeared in several films since making his big-screen debut as the star of Hudson’s Lost Angels, but his acting career has never sparked the way his music work did. Watching Lost Angels today, it’s striking just how moving and resonating Horovitz’s work is, particularly considering a lone role on television’s The Equalizer was his only real previous experience. His performance in Lost Angels has a real rhythm and grace to it and it’s hard to not feel a tinge of regret at the thought he never had the chance to capitalize on it, although he came close with Abbe Wool’s equally in need of rediscovery Roadside Prophets (1992).

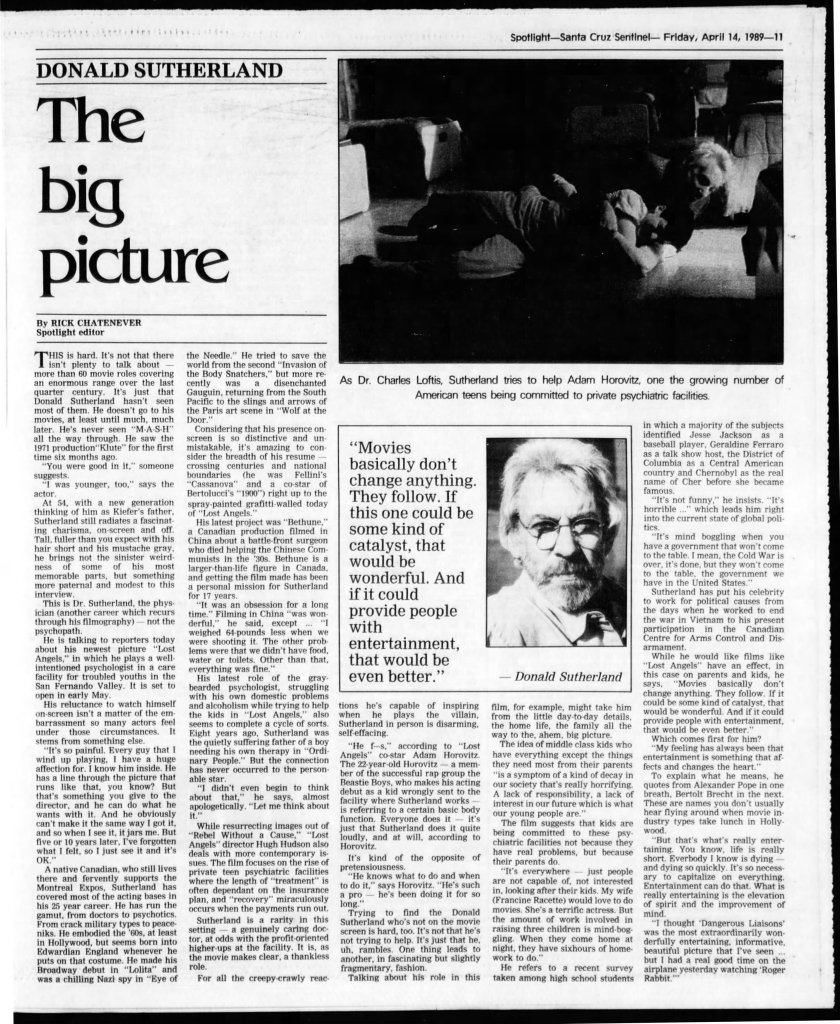

Lost Angels received minor pre-release coverage in the spring of 1989 leading up to its successful Cannes premiere. A lengthy profile of Donald Sutherland appeared in The Santa Cruz Sentinel by Rick Chatenever. The remarkable Sutherland previously worked with Hudson in Revolution and it is much to his credit that he returned to the fold after that film’s violent reception. Praising Hudson’s message with the film, Sutherland noted, “Movies basically don’t change anything. They follow. If this one could be some kind of catalyst, that would be wonderful. And if it could provide people with entertainment, that would be even better.” Horovitz was also quoted in the lengthy profile, which can be read below:

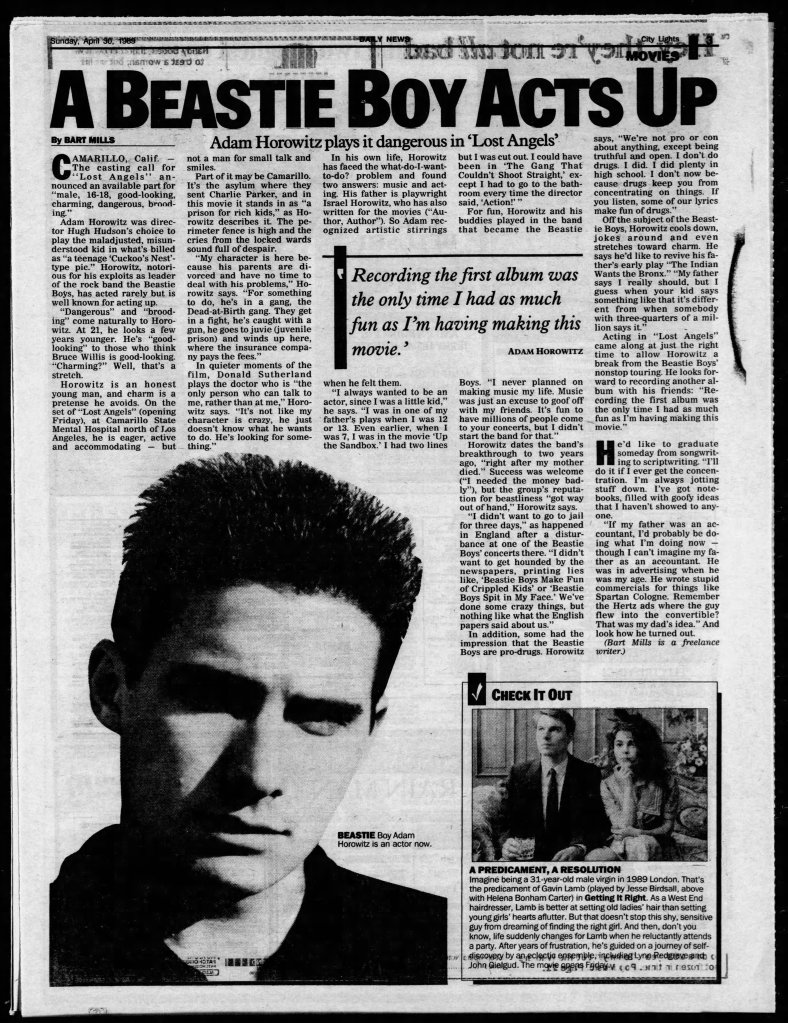

Hudson dedicated Lost Angels to his then ten year old son making it all the more personal. He told Parade that “it is terribly painful today to be a parent, as well as a child” and he lamented being away from home so much making films. Profiled in The New York Daily News, Horovitz picked up on the importance of a missing in action parent in Lost Angels pointing out, “My character is here because his parents are divorced and have no time to deal with his problems”. The son of playwright, Israel, Horovitz recalled, “I always wanted to be an actor, since I was a little kid. I was in one of my father’s plays when I was 12 or 13. Even earlier, when I was 7, 1 was in the movie Up The Sandbox. I never planned on making music my life. Music was just an excuse to goof off with my friends.”

Upon Lost Angel’s release, few critics were in the mood to come to Hudson’s defense although most of the notices were mixed. A typical review arrived in The San Francisco Bay Guardian where critic Steve Warren complained that Horovitz was “unexpressive” but gave the film a mild passing rating. Most critics couldn’t help but pick on Hudson though such as The 1990 Motion Picture Guide:

“Lost Angels is crippled by an unresolved schizophrenia at every level, its depiction of a grim, amoral subculture undercut by lush photography and sinuous camerawork. British director Hugh Hudson working from a script by playwright Michael Weller, can’t seem to figure out whom to hold accountable— at times he indicts the indifferent, self-absorbed authority figures, and at other times he points a finger at the incorrigible youth. Moreover, the film’s uneven tone and languid rhythm are at odds with the subject it explores. At almost every opportunity, the film opts for the sensational at the expense of nuance and irony. Hudson has obviously made Lost Angels more out of sorrow than anger, and that’s a large part of the problem. His sympathies are so diffuse, they become confused; Lost Angels is a film with as little sense of direction as the youth it depicts.”

Giving the film a five out of ten rating, Fort Worth Star-Telegram critic Michael H. Price called Lost Angels “courageous” but complained the film’s ‘upbeat’ ending badly let it down, a valid point considering the ending is Lost Angel’s weakest element. Boston Globe critic Jay Carr found less to love in Lost Angels, awarding it just a star and a half although he found Horovitz ‘impressive.’ Carr noted the film could have been a ‘contender’ were it not for the ending.

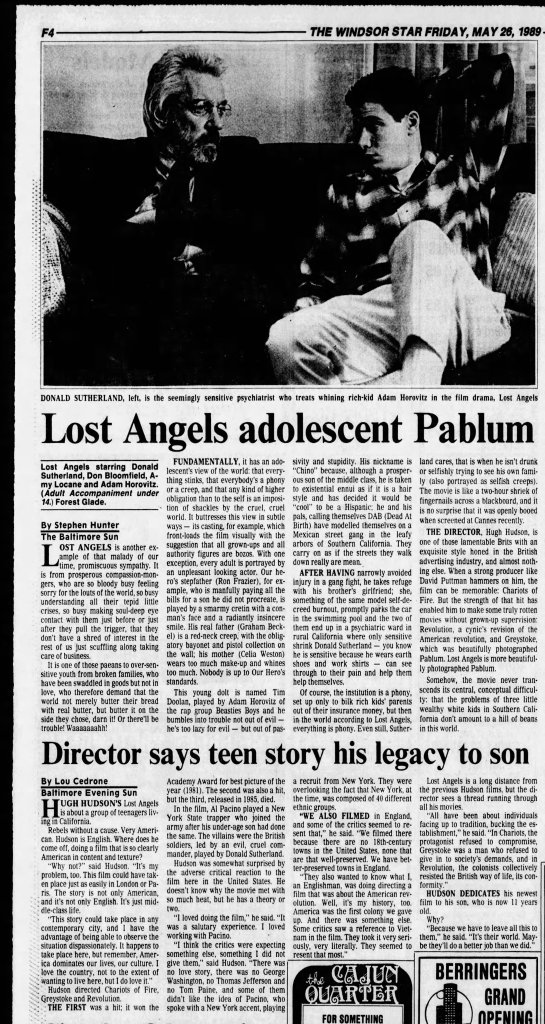

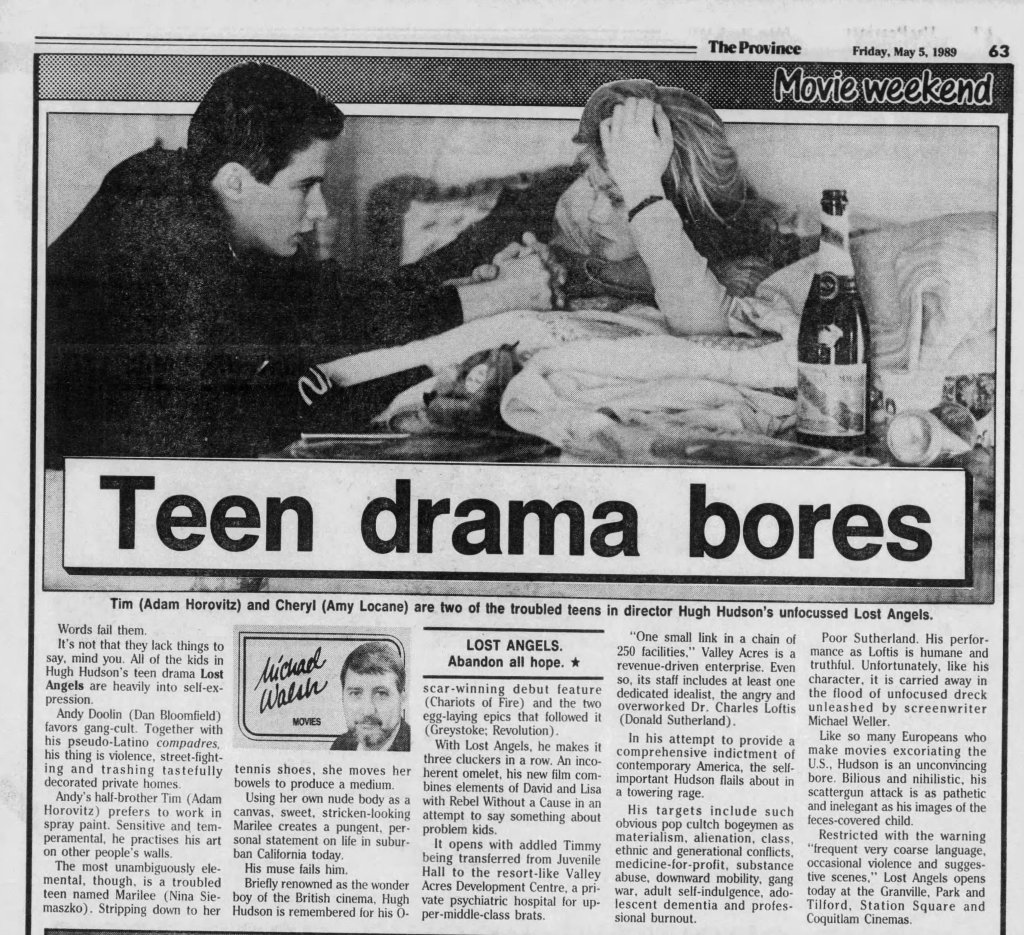

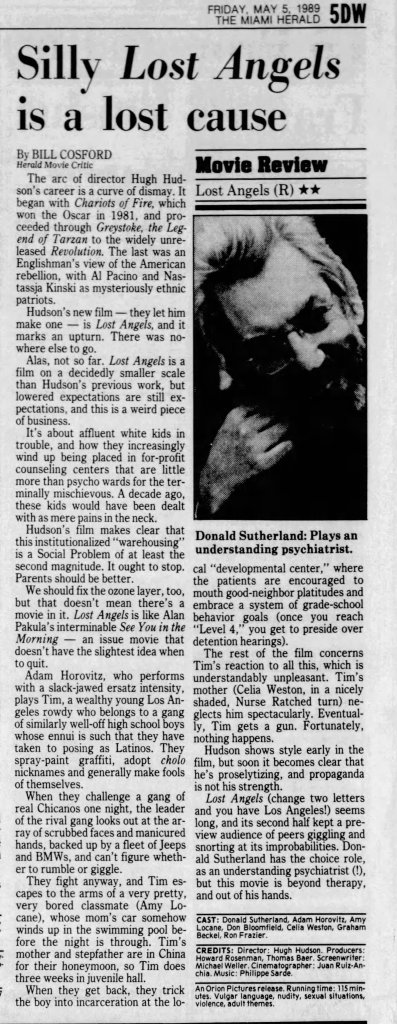

More mixed to poor reviews continued as Lost Angels struggled to find its box-office footing. Miami Herald critic Bill Cosford praised parts of the film’s early moments but said the film was ultimately “beyond therapy.” Canadian critic Michael Walsh echoed Cosford’s thoughts calling Lost Angels Hudson’s “third Clucker in a row” before finally referring to the great British filmmaker an “unconvincing bore.”

Lost Angels continued taking a critical pounding throughout 1989. Baltimore Sun journalist Stephen Hunter praised the film’s photography but little else. Still proud of his string of failures, Hudson exclaimed to Baltimore Evening Sun writer Lou Cedrone that all his films were about “individuals facing up to tradition, bucking the establishment.” Hudson was clearly talking about himself as well, as he watched yet another one of his fine works face rejection.

Roger Ebert joined the growing voices complaining about the film’s ending in his two and a half star review. Praising the way Hudson avoided “obvious cliches”, Ebert also appreciated how the characters were treated with “dignity”. He finally noted he found Lost Angels an “intelligent well crafted film” that ultimately didn’t move him although he praised the performances.

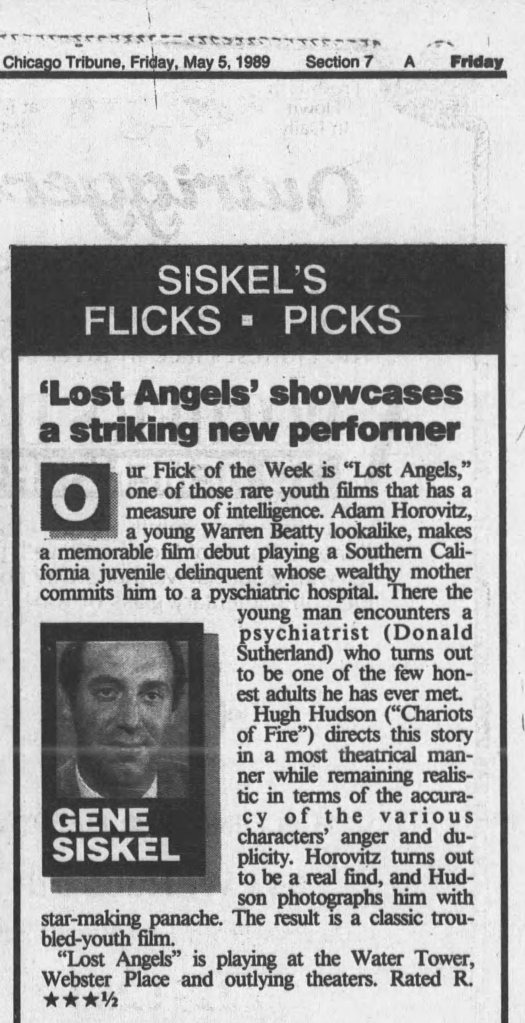

Ebert’s partner across the aisle, Gene Siskel, was amongst the critics who loved the film calling it an absolute “classic troubled youth film” in his near four-star review, especially praising Horovitz as a real “find.” Siskel was amongst the few American critics completely won over by the film but that wasn’t true in France, where Lost Angels made much more of an impact thanks to its strong showing at Cannes (although boos were heard at its screening). A defiant Hudson appeared at the Festival calling his film deliberately “confrontational” and he wanted it to be “upsetting” to the middle and upper class. Most shockingly, Hudson admitted that the film was also an indictment against himself, “a successful middle classed man who in some ways put his career before family.”

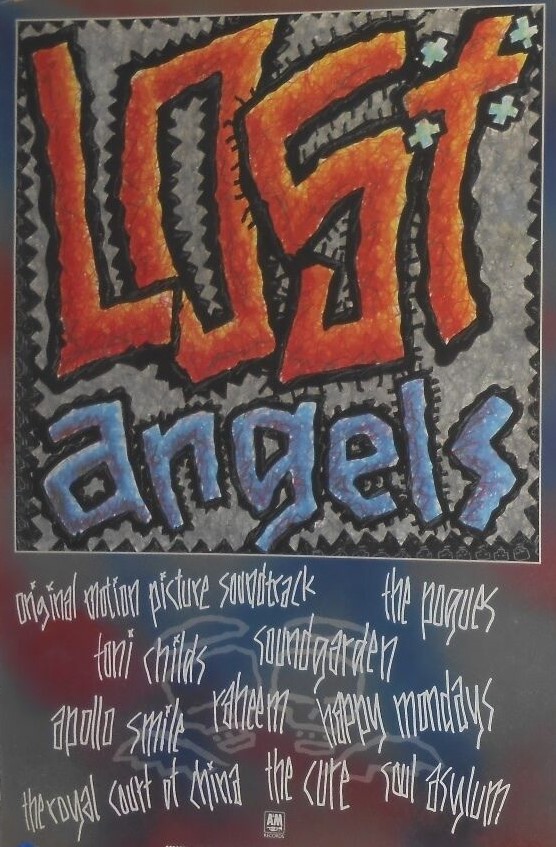

The positive buzz around Lost Angels at Cannes faded fairly quickly and by the fall of 1989 it had barely earned a million bucks despite a substantial theatrical release for an independent film. Not even a CD soundtrack featuring a number of the period’s best artists helped.

After the relative failure of Lost Angels, Horovitz stepped back into his iconic role as a Beastie Boy and within a few years would help solidify the group as one of the greatest in rock history. His role in Roadside Prophets remains his sole starring role outside of his powerful turn in Lost Angels.

Hugh Hudson would drift away from film for nearly a decade before his sweetly stirring return with the lovely My Life So Far (1999), another fine work few took note of. After a couple of other features, Hudson ultimately returned to the world of documentary filmmaking with the very personal Rupture: A Matter of Life Or Death (2011). By the time Hugh Hudson died in early 2023, he had gained some of but certainly not all the deserved respect that had been stripped from him in the mid-eighties.

Lost Angels was released on VHS and laserdisc in the early nineties and finally on DVD in 2012. To my knowledge it had never had an HD home video release and it currently isn’t streaming. One of the great unknown American movies of the late-eighties, Lost Angels is quite a special little film and I would love to see it resurface one day to finally find the audience it has always deserved.

-Jeremy Richey, 2024. Revised and expanded from a Moon in the Gutter piece I wrote back in 2014-

Here are some further articles, quoted from above.

Leave a comment